Are a Bunch of Law Schools About to Shut Down?

I started digging into the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) a few days ago thinking I'd write about its impact on student loan markets. What I found instead was more interesting: a provision that could force the closure of many law schools, depending entirely on how the government defines the phrase "same field of study."

There's no markets angle here - the post-2010 student loan program killed the secondary market when the government moved to originate-to-hold. But the underlying problem is precisely the absence of market discipline, and the solution Congress chose reveals how hard it is to impose accountability through administrative rules when market mechanisms don't exist. The specific problem: trying to apply a median earnings test to a field where salaries follow a bimodal distribution, rendering the median statistically meaningless.

Changes in Student Loans Since 2010

First, a short history on student loans.

Prior to 2010, U.S. student loans were very similar to Agency MBS—private loans, made by a bank, with a government guarantee of repayment if the borrower went into default. Since they had embedded prepayment options (the borrower could pay the loan off early if they wanted), they had similar duration and negative convexity characteristics to mortgage bonds.

Post-2010, the federal government makes most student loans directly from its own balance sheet, with servicing handled by private sector operators. (There is a small private refi market.) The negative convexity profile is similar, with borrowers long an embedded prepayment option. The two main implications:

- Since the government originates-to-hold on student loans, there is no real secondary bond market anymore for post-2010 student loans, and therefore no price discovery mechanism for the true cost of these loans; and

- The government is effectively running a net interest margin (NIM) business, with student loans rates being set based on the 10-year Treasury auction in May (spreads at 10y Treasury +200-450 bps depending on type of loan), and funded by the weighted-average yield on Treasury securities.

Lending at say 7%, while your funding costs 4% and has no equity requirement looks like a fantastic business on paper, but somehow the government loses money on student loans. How is that possible?

Student Loan Nonpayment Rates Are Crazy High

Some facts about student loans in the U.S., as of September 2025:

- $1.7 trillion of loans outstanding, growing at 7% per year since 2007

- 42.8m total borrowers

- 73% of borrowers have $40k or less total student loan debt

- Only 53% of student loan borrowers that are eligible to pay (meaning they are not in school, in the post-graduation grace period, or do not have deferred loans because they have returned to school) are paying

The Department of Education has estimated that student loans issued in 2025 will default at rates of 14-29%, depending on the type of loan, with ultimate recoveries of 65-75%. These default rates far exceed any category of private sector lending, including junk bonds.

Ultimately, these losses are eaten by the taxpayer, and given how large and widespread they are, can be thought of as a subsidy or educational grant.

The “Gainful Employment” Test Under OBBBA

The fact that, in many cases, the government student loan program provides a poor return on investment (ROI) to both taxpayers and borrowers has been known for some time. Congress introduced the “gainful employment” rule during the Obama administration, which suspended loan eligibility for students attending private colleges (think University of Phoenix) or non-degree programs at nonprofit colleges under the following criteria:

- If annual loan payments exceed

- 20% of discretionary income, and

- 8% of total earnings

- For 2 out of 3 consecutive years

The original gainful employment rule (which still exists) is essentially a “debt-to-earnings” metric, testing whether a graduate of one of these programs can support debt service. Importantly, it does not test if the time and money spent in school increases a student’s earnings.

Changes to Gainful Employment

The OBBBA makes two major changes to the gainful employment rule.

- First, the rule now applies to all institutions that receive federal student loans—private, public, and nonprofit schools.

- Second, programs must increase graduates’ absolute earnings to receive federal student loan dollars. Failing the test 2 out of every three years triggers a loss in funding.

For undergraduate programs, students must beat the median earnings of high school graduates in the state to continue receiving federal funds. As a practical matter, every halfway decent undergraduate college should meet this test—the high school median earnings are very low, with Mississippi at $27k/year at the low end and New Hampshire at $38k at the high end.

Graduate Programs May Feel the Bite

While undergraduate programs will likely escape unscathed by the new rule, master’s programs may not. From AEI, emphasis mine:

For graduate programs, the benchmark is equal to the median earnings of working individuals age 25 to 34 who have only a bachelor’s degree and are in the same state as the institution, have an undergraduate degree in the same field of study as the program, or are in the same state and field of study. The benchmark is the lowest of these three options. Again, the benchmarks are calculated based on national populations if more than half of students at the institution are out of state.

These benchmarks are applied at the program level. A school’s engineering program may pass the earnings benchmark test, while the gender studies program fails. The law empowers the secretary of education to group small programs together in order to achieve a minimum sample size for measuring graduates’ earnings.

Simplified, what this law is saying is that if I am a university and I offer a master’s degree in psychology, my graduates have to earn more than people in the same state with a bachelor's degree in psychology. If they don’t earn more than people in the same state who could have done the same work without a master’s degree, and that happens two out of any three years in a row, then future students in my program lose access to federal student loans.

Implications for Law Schools

There are two reasons why this law may impact law schools more harshly than other programs: the bimodal distribution of legal salaries and master’s-level training being required to become a lawyer in the U.S.

The Bimodal Distribution of Law Salaries

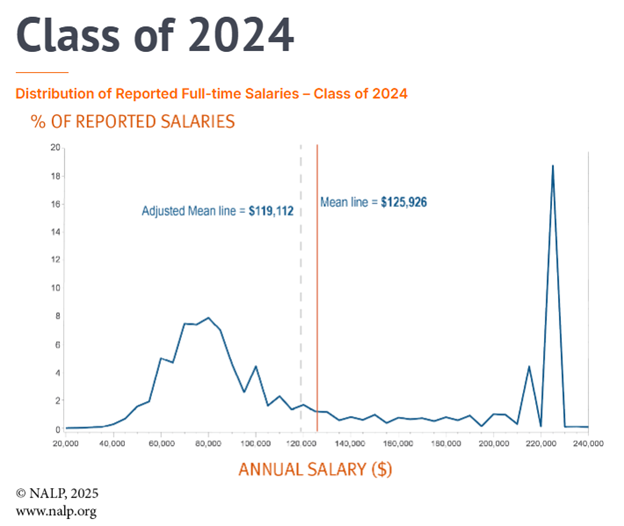

Salaries for new law graduates look strange compared to other fields:

Source: National Association for Law Placement (NALP), Class of 2024

The 18.7% of reported salaries at $225,000 represent the starting salary for “BigLaw” firms, which are the 100 or 200 largest corporate law firms in America. Traditionally, a firm called Cravath, Swaine & Moore announces its starting salary for new hires, and within weeks, every other BigLaw firm matches their starting salary to Cravath. This is called the “Cravath scale.”

This lockstep system exists because BigLaw clients pay premium prices for elite credentials as a form of risk mitigation. Rather than compete on associate salaries, firms compete on prestige and implicit quality guarantees. Regardless, it means that if you are one of the top 10-15% of graduates (this data contains only reporting students, about 25,000, while U.S. law schools graduate about 35,000 students per year), you are fixed at the Cravath scale.

According to NALP, 53% of law graduates earn $55,000-100,000, putting the median in this range. Schools that send a large portion of their graduates (traditionally the top 14 law schools) to BigLaw will have average salaries close to $225,000. Everyone else will have average salaries in the lower peak and are guaranteed to fall below the OBBBA’s median calculation, if the state in question has any meaningful corporate law presence.

The disparity is more extreme in major markets. In New York state, NALP data show that the BigLaw peak is nearly 3x higher than the national figure. That means low-tier law schools in NYC could have graduates earning $65-70k competing against a state median inflated by BigLaw associates earning $225k.

The core problem here is that the median is not a meaningful statistical tool when we are dealing with a multimodal distribution. It’s like saying that water is at a pleasant average temperature when half is freezing and half is boiling.

Bottom-tier schools demonstrate the disconnect. Thomas Jefferson School of Law and Cooley Law School both have nonpayment rates of only 6-7%, far better than for-profit schools like the University of Phoenix (24%). However, borrowing $150k of student loans to earn a salary of $55k is not a good return on investment, even if the borrower somehow keeps their head above water.

Law as a Master’s Degree

In America, almost every new lawyer has a J.D., or Doctor of Jurisprudence. There are no bachelor's degrees in law.

Under the new OBBBA rule, the only relevant test is whether a law school produces median earnings higher than others “in the same state and field of study.” (If a school has more than 50% of its students coming from out of state, then the earnings are compared to a national median.)

- If “field of study” (which will be defined by the DoE through regulatory rulemaking) means only other lawyers, then 50% of law graduates will definitionally fall below the median earnings of lawyers in the same state; however,

- If “field of study” includes all legal occupations, like paralegals, secretaries, and court staff, then weaker law schools have a much better chance of retaining access to student loans. (In NYC this still won’t help, since paralegals in BigLaw earn at or above lawyers at smaller firms.)

My sense is that the DoE will have to include the broader definition of “field of study,” because a strict definition would mean the closure of at least a third of the law schools in America.

Conclusion

Since the student loan market is now entirely government-controlled, there are no market mechanisms for price discovery and risk measurement. Since ~14-29% of student loans default, and nearly half have periods of nonpayment, a good portion of educational lending does not provide good return on investment.

Congress has introduced an earnings test to address the excess, but the measure is flawed as applied to the legal field because a median is not a meaningful statistical measure when applied to a bimodal distribution.

Furthermore, even if the DoE expands “field of study” to include paralegals, lower-tier schools in big markets such as New York, Texas or California risk failing the test and be forced to close as they are competing against state medians inflated by BigLaw salaries.

Administrative rulemaking is not well-suited to creating market discipline. It’s impossible when the rule depends on statistical measures that don’t work for the underlying distribution.