So are electric vehicles a good buy or what?

TL;DR – electric vehicles are already cheaper than comparable gas cars when viewed from a Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) perspective. If you are in the market for a new car and have been reluctant to consider an EV because of the price, do the math (or read this post) before you jump to any conclusion about what is expensive and what isn’t.

---

I got in a wreck recently and had to get a new car. I asked an experienced dealer (Aaron) what cars he thought would hold value, and he surprised me by saying that he thinks that internal combustion engines (ICE) will be going the way of the dodo. The analogy he used was “in 1910, what horse and carriage would have held the best value?” (The Ford Model T was launched in 1908.)

I asked him what the issue with ICE cars is, and he said that internal combustion engines simply have a lot of moving parts and as a result things break and require maintenance. Fundamentally, the internal combustion engine is a 100-year-old technology that hasn’t seen quantum leap types of improvements since its invention. Aaron’s theory is that rather than most people buying a new car every 10 or 15 years, people in the future will buy an EV and use it for 30 or 40 years. The EV battery would need to be replaced periodically but most of the other components wouldn’t. By comparison, a gas car has a useful life of 200,000-300,000 miles or so. He thought the EVs of the future would have useful lives far past 300,000 miles. Not only that, but parts of the EV that require upgrades—like software—would just be updated remotely by the manufacturer in the same way that your iPhone or laptop just updates software automatically.

All this made me curious about the cost as of today: how do EVs stack up against gas cars?

The Argonne National Laboratory report

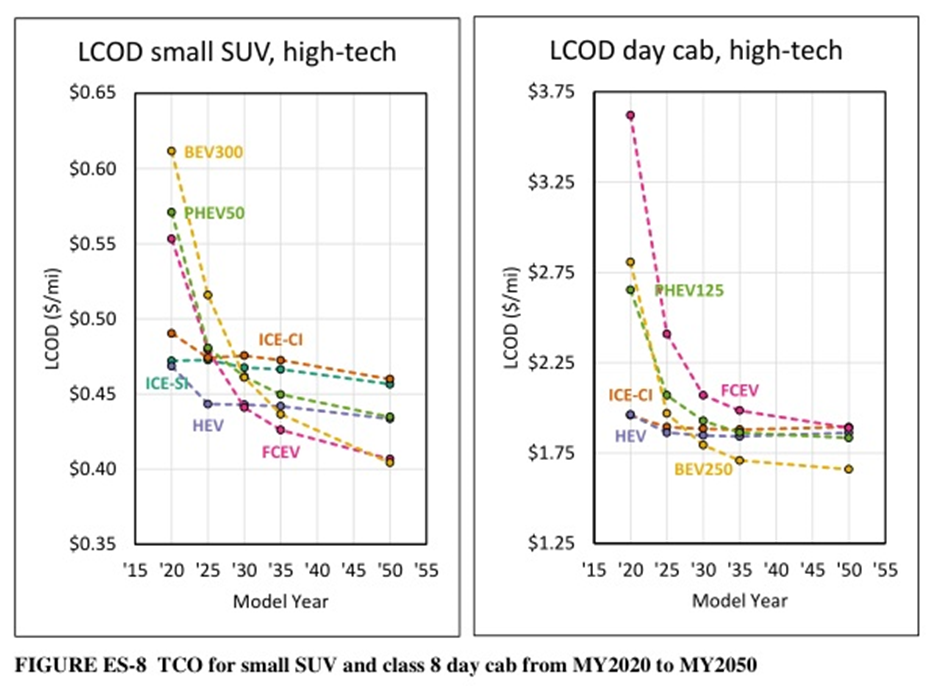

To my delight, I found a 227-page report from the Argonne National Laboratory (ANL) covering exactly this topic. (Our government really does fantastic work in some respects.) The ANL report evaluates the cost tradeoff between powertrains (various ICEs vs. EVs) using two main metrics, Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) and per-mile Levelized Cost of Driving (LCOD). The TCO is just the total dollar amount it will cost you to operate the vehicle for 15 years (driving 12,000 miles per year) considering all expenses, including maintenance, fuel, taxes, insurance and so on. The LCOD is the same analysis, just calculated as a per-mile cost.

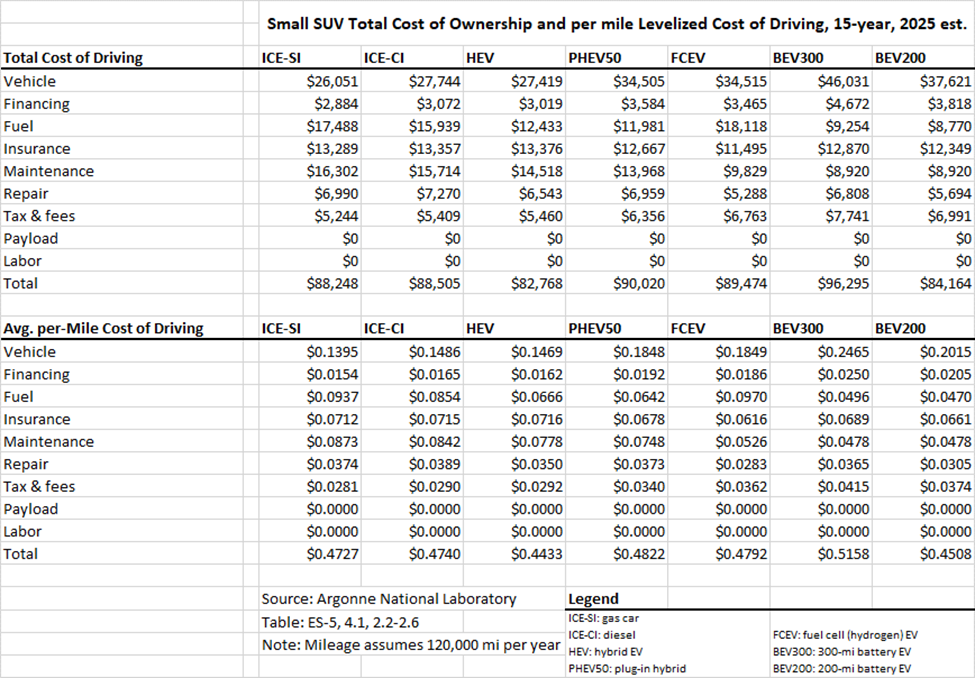

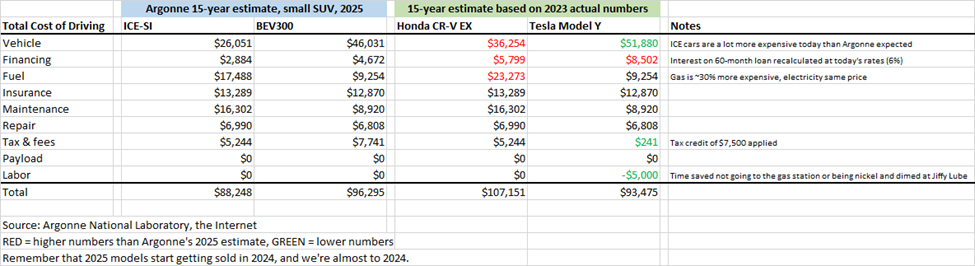

In short, based on their analysis from April of 2021, ANL expected EVs to be close to competitive with gas cars by 2025. ANL estimated that for a small SUV, their baseline vehicle, a normal gas car would cost $88,248 to operate for 15 years, while a 300-mile EV would cost $96,295, a difference of about $8,000.

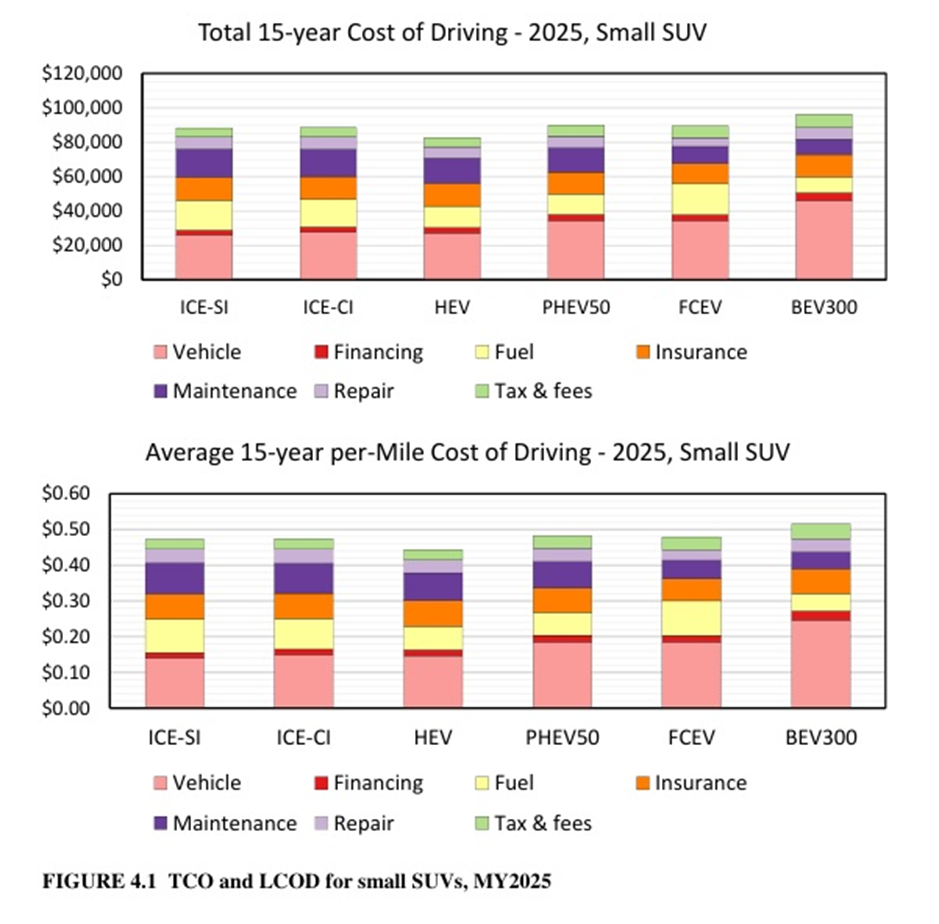

Here's a helpful graphic from the report:

Legend: ICE-SI = Internal Combustion Engine-Spark Ignition (gasoline); ICE-CI = Internal Combustion Engine-Compression Ignition (diesel); HEV = Hybrid Electric Vehicle; PHEV50 = Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle; FCEV = Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle (hydrogen); BEV300 = Battery Electric Vehicle-300mi Range

Two takeaways from this chart. First, hybrids (HEV) are the cheapest vehicles to operate. My family’s positive experience with hybrids at least anecdotally supports ANL’s findings. Second, the higher TCO of the 300-mile EV (BEV300 in the chart) is driven by the higher up-front cost of the vehicle, which largely comes from the expense of the battery. In the case of the ICE-SI (internal combustion engine-spark ignition, i.e., a normal gas car) the cost is driven by higher maintenance and fuel costs, consistent with what Aaron told me.

Here are the raw numbers:

However, all of the above numbers were 2020-2021 forecasts of what things would look like in 2025. My view is that ANL significantly underestimated the cost of owning a gas car and overestimated the cost of an EV (not their fault, forecasting is hard). Plugging in prices from today, and using actual comparables—the small SUV Tesla Model Y vs. the small SUV Honda CR-V EX—the EV comes out cheaper already. The rest of this post walks through the analysis.

Maintenance costs

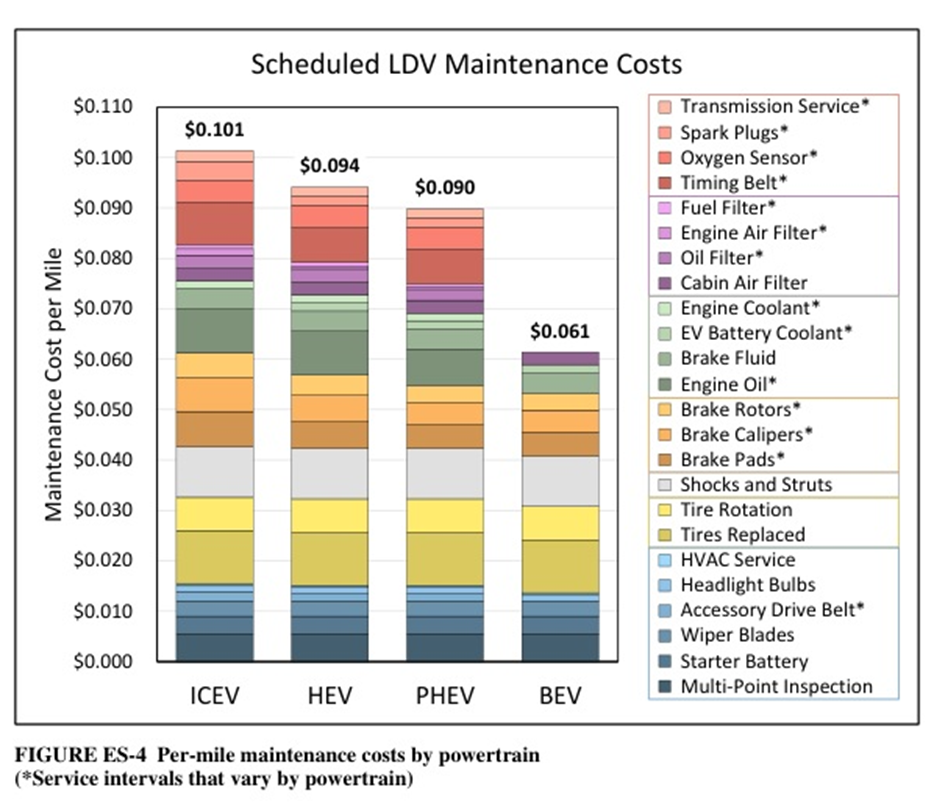

The bottom line is that EVs are much easier to maintain than ICE vehicles. Argonne has a useful chart demonstrating maintenance expenses by powertrain (LDV = light-duty vehicle):

Car maintenance is annoying. I hate dealing with it. Among other things, a pure battery EV avoids maintenance on transmission, spark plugs, oxygen sensors, timing belts, engine coolant, fuel filters, engine air filters, oil filters, and engine oil. All of this adds up to a maintenance cost per mile of 4c less, or $7,500 less over the 15-year life of the vehicle. This also doesn’t count the time needed to take the vehicle into the shop to get all this stuff done. Assuming that you have to get some of this stuff done every 5,000 miles on a gas car, and taking your car into the shop costs you 2 hours counting travel and waiting time, that’s 36 visits to the shop over the life of the car and 72 hours of time in your life you’re not getting back. Most professionals who read this blog can safely value their time at $100/hour or more. That comes out to another $7,200+ in lost time.

Fuel costs

Argonne’s 2021 fuel cost estimates are based on a price of $2.63/gallon for gasoline and $0.13/kWh for residential EV charging. The gasoline estimate was… optimistic. In Austin, regular unleaded gas is $3.50/gallon at the time of writing (30% more expensive) while the kWh estimate is roughly accurate for Texas. Gasoline prices are notoriously difficult to predict but between inflation and the Saudis cutting oil production whenever they feel like it, I’ll go out on a limb and say that gas isn’t going back down to $2.63 on a consistent basis ever. Assuming gas stays at today’s price, that takes the fuel portion of an ICE car’s TCO up from $17,488 to $22,734—a $5,000+ increase.

Electricity prices are also difficult to predict, but a big portion of the input costs are almost certain to continue going down. ANL’s estimate of 13c per kWh is lower than the U.S. average of ~17c/kWh but is at least accurate for Texas (gas prices are also higher than $3.50 elsewhere in the country). As for industry forecasts of wholesale power costs, I’ve seen both estimates of lower prices over the next 5-10 years as more and more solar PV gets built, as well as long term forecasts of much higher prices due to electrification demand and climate change. Regardless, I’m optimistic about electricity as an input cost for EVs because the driver in many cases will have the option to charge the vehicle when power prices are lowest (wholesale electricity prices vary throughout the day due to supply and demand factors).

The powertrain’s efficiency also matters, not just the price of the fuel. A Model Y gets about 3.5 miles per kWh—at 13c/kWh, that comes out to 3.71c per mile. A Honda CRV gets about 30 mpg, so at $3.50/gallon, that comes out to 11.67c per mile. Argonne forecasted an ICE small SUV to pay about 2x the fuel cost of an EV, but my rough math suggests the fuel cost of an ICE SUV is closer to 3x of an EV.

Battery degradation is also an issue, as anyone who has used an old laptop or smartphone knows. Aaron thinks that we’ll get to a point in the future where batteries can easily be replaced in an EV, much more easily than a new engine can be put in a gas car. Regardless, for the older Tesla models, I’ve seen anecdotal discussion that degradation is about 12% after 200,000 miles driven. That seems very low to me, compared to how worn-down laptop and phone batteries get after a few years of use as well as how much degradation we model in utility-scale batteries.

The last comment I want to make on fuel relates to the time spent refueling the vehicle. Filling up the gas tank takes about two minutes, while charging a Model Y can take anywhere between 30 minutes and a whole week depending on the type of charger. For ordinary city driving it seems easy to just charge the car at home while you’re sleeping (power prices tend to be very low around midnight-2am when the wind is blowing strong but almost everyone is asleep). For me, the upside to charging at home is that I never need to think about visiting the gas station again. The downside, of course, is range anxiety—I wouldn’t want to take an EV on a road trip from Texas to Wyoming. That might change one day if we have superchargers as ubiquitous as gas stations, or if we find a way to efficiently slap solar panels on the roof of a car.

Vehicle costs

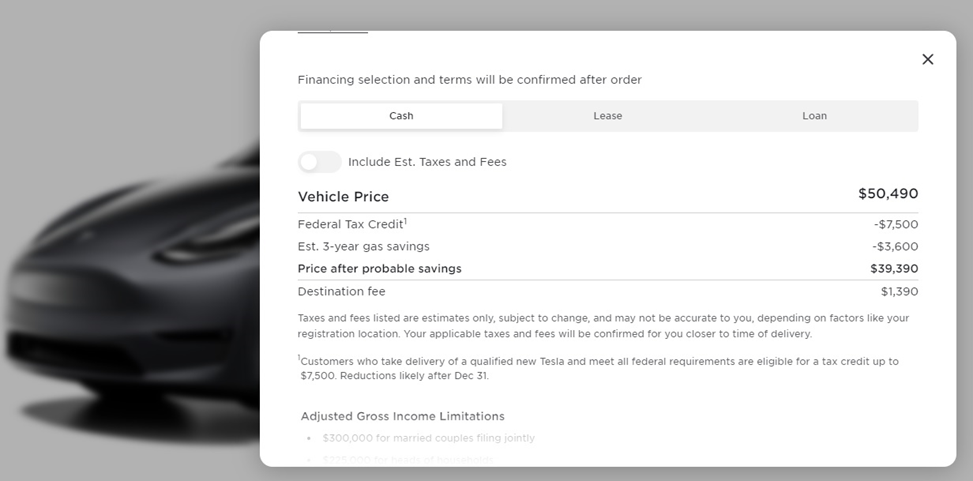

Argonne estimated that a gas small SUV would cost $26,051 in 2025 while a BEV300 would cost $46,031. To test this, I looked at two popular small SUVs that I assume are roughly comparable (dunno, I’m not a car guy): the Honda CR-V EX and the Tesla Model Y. Here are the prices today:

The Argonne study didn’t consider the $7,500 EV tax credit from the Inflation Reduction Act. Factoring that into the Tesla price but backing out their estimate of gas savings (since we’re analyzing that separately) the Model Y comes out to $44,380. Reasonably close to the Argonne estimate. However, they wildly underestimated how much gas car prices would go up during the pandemic:

Source: TrueCar

This is $10,000 more expensive than the Argonne estimate. Like gas and electricity prices, I know there have been some significant swings in vehicle prices over the last few years. I don’t know if they are here to stay because of inflation and permanently disrupted supply chains or if car prices will fall again. In the case of electric vehicles, at least, Argonne thinks they are set to fall drastically over the next decade:

The rapid drop in forecasted BEV prices comes from assumptions about how quickly lithium-ion battery prices will fall, since the higher up-front cost of the BEV is driven mostly by the expense of the battery pack. Argonne estimated battery pack costs of $170/kWh in 2025 for cars, but BloombergNEF is estimating that battery pack costs are already down to $151/kWh as of 2022. For reference, the Model Y’s battery pack is 81 kWh with a 330mi range. Using Bloomberg’s numbers, that implies the battery pack itself costs $12,231, or nearly 25% of the retail price of the vehicle. Assuming fuel prices held with their $2.63/gallon estimate, Argonne forecasted that EVs would reach cost party with gas cars when battery pack prices hit $98/kWh around 2035.

I think EVs are already significantly cheaper than gas cars—if you can deal with range anxiety, you should buy one

Updating Argonne’s estimates with today’s actual prices for cars, gasoline, interest rates, and tax incentives, plus adding what I think is a conservative estimate on maintenance time savings, we get this:

Even if you throw out my $5,000 of time savings, or balance that against range anxiety, you still get a TCO for an electric vehicle that is almost $9,000 lower than a comparable gas car. And it’s possible the Model Y and Honda CRV are not actual comps—the Model Y (might) be a nicer car to begin with.

This is a good deal!

A closing word on the car dealership model

The car dealership model in the U.S. is probably worth a blog post on its own. I don’t exactly know the reasons but in the United States, the majority of carmakers are not allowed to sell their products directly to the consumer but are required to go through third-party companies known as “auto dealerships.” If I buy a Honda I’m not buying it from Honda, I’m buying it from a middleman that is required to exist because of state law.

Aaron told me that car dealerships are pretty hostile to EVs because they require much less recurring maintenance and therefore provide a much lower recurring revenue stream to the dealership. Many don’t stock EVs from any manufacturer and their sales force often knows little about the advantages and disadvantages of driving electric. Not only that, but some states have exceptions that allow EVs to be sold directly to the customer (like Tesla), bypassing car dealerships and the associated markups.

Car dealership associations are politically powerful at the local level and some dealership owners become politicians themselves (name recognition is a big factor in electability). One implication of dealers being hostile to EVs is that they can influence state-level laws to be hostile to EV adoption in various ways. Just something to think about.

I have a follow-up post about EV adoption macro trends and what it means for the electricity grid.